South Dakota Legislators Consider State Coverage for Inmate Legal Defense Fees

South Dakota lawmakers explore shifting responsibility for inmate legal defense fees from counties to the state.

Hypothetically, let’s say that one of your close family members was hanging out with the wrong crowd. You’ve told them time and time again that they shouldn’t hang around these people, but they won’t listen. Then one night you get a call and find out they got picked up by the police for a felony residential burglary when they were with their “crew”. Soon after, they’re convicted and sentenced to five years in prison. While in prison, you visit them numerous times and they say how it was a dumb mistake and they’re going to turn their life around once they get out of prison.

…Fast forward five years…

You’re at the gates of the institution, they served their time and you’re picking them up to leave the prison. They’re thrilled to see you and exclaim how amazing it is to be free.

Six months go by and everything is fine. They’re struggling to find a job, but they seem to be in good spirits. They’ve ditched their old “crew” and they’re trying to straighten their life out.

Then, right around nine months of being released from prison, you find out that they were arrested at a local Walmart for stealing $800 worth of merchandise and charged with another felony, which lands them back behind prison doors.

This is a perfect example of recidivism and it’s a problem often overlooked.

The dictionary defines recidivism as; a tendency to relapse into a previous condition or mode of behavior especially: relapse into criminal behavior

Simply put, it’s the act of someone with a criminal past re-offending and, in many cases. returning to prison.

The scenario at the beginning of this post was a hypothetical, but situations like this are frighteningly common.

What if we told you that there was a study done by the Bureau of Justice Statistics over the course of nine years that showed that within the first year of release, 43.1% of former inmates were arrested again?[1]

Not only that, but this same study showed that within nine years of release, 83.4% of former inmates will be arrested again.

There are many reasons why this happens, but it seems contrary to what former inmates would want to happen.

This is one of the most difficult questions to answer because recidivism isn’t caused by just one factor.

The actual cause of recidivism can be tied to a combination of personal, economical, sociological, and lifestyle factors.

Social Interactions While Incarcerated: While incarceration is focused on punishing and rehabilitating prisoners, one of the most detrimental factors to proper rehabilitation can be the social interactions that inmates have while incarcerated.

When someone first gets incarcerated, they may have a been associated with a limited social circle of amateur criminals, but prison offers a network of career criminals that could further their criminal prowess. If an inmate isn’t actively resisting criminal tendencies and trying to rehabilitate themselves, they may learn more about how to become a better criminal and, upon release, return to a life of crime.

This return to crime typically ends up with another arrest as roughly 68% or former inmates get arrested within their first three years of release [2].

Lack of Employment: When someone finally gets released from prison, even if they want to live a normal life and be a productive member of society, their employment options are severely limited.

It’s estimated that an individual who has a felony on their record reduces the likelihood of getting a call back from employers by 50% [3].

These lack of employment options lead to a lack of finances.

This lack of finances leads former inmates into desperation and desperation leads to crime.

Incarceration Doesn’t Treat the Problem: While many institutions state that their goal is to treat inmates and rehabilitate them, anecdotal evidence from JobsForFelonsHub.com suggests that most inmates don’t feel rehabilitation is part of the experience.

In addition to the lack of proper rehabilitation, 2 million people every year are added to the jail system that have a mental illness [5]. How many of these individuals end up in prison is a statistic that we can’t find, but it’s reasonable to assume that there is a correlation.

The National Center of Addiction and Substance Abuse at Columbia University estimates that of all incarcerated individuals with substance abuse issues, only 11% of those that need treatment actually receive it while incarcerated [6].

Depression and Desperation: With all of these mental issues abound in prisons, where certain studies have estimated 31% of females and 14.5% of males have a serious mental issue [7], without proper treatment these issues will carry over into when the inmate is released.

The lack of employment, negative social stigmas, and lack of support upon release can put inmates into a deeper state of depression and lead to desperate attempts to get the things that they want such as drugs or finances.

Being Overwhelmed by Society: For those that have served long sentences in prison, it’s not surprising that some inmates are intimidated and overwhelmed upon released.

Being incarcerated forces an individual into a rigid schedule and they are required to follow rules every single day.

While the monotony is undoubtedly tiresome, it also doesn’t give inmates the chance to have freedom of choice.

Once they are released, aside from regular meetings with a parole officer, they have much more freedom and this can lead to them feeling overwhelmed and full of anxiety.

This feeling may lead to substance abuse to cope with these issues. That substance abuse can result in additional crimes to fund their dependency, which will ultimately lead the former inmate back into prison.

Not Changing Lifestyle/Social Circle Upon Release: Part of a successful rehabilitation is for individuals to distance themselves from negative influences upon release. These bad influences can come in many forms, but the key is for those who have been incarcerated to find a new support group to associate with.

Unfortunately though, this is much easier said than done. Many times, former inmates will go back to the same crowd of people they used to associate with because finding a new group isn’t easy to do.

Beyond that, it’s unlikely that a new group would be as willing to help as their old crowd, thus it’s natural for the former inmate to not change the group they hang out.

Further, if gang activity is involved, it might be very difficult to leave their old group for fear of retribution.

All of these issues compound on to each other and with each issue included in the individuals release, the lesser of a chance that they have to not be a statistic of recidivism.

Though this is a simple question, it isn’t a simple answer. There have been many studies done to try to determine the national recidivism rate.

First, there are over 10,000 prisoners released from state and federal prisons every week. [2] That said, trying to keep track of over 40,000 people every month and whether they re-offend isn’t realistic. There are too many variables at play.

Second, there are times when a former inmate will commit a crime that goes undetected. Because the recidivism rate is only detectable if a person is arrested, it’s not possible to accurately record all instances of crime.

There are ways to measure recidivism with more accuracy, but they aren’t financially viable and can be skewed due to subject responses.

For example, a team could interview all subjects of the study on a regular basis, but to come to any meaningful conclusion you’d need a very large data-set. This causes numerous issues because of the finances involved and the fact that many of the subjects may forget things over time or not be willing to tell the truth in all cases.

All these factors considered, there was a very in-depth study by the Bureau of Justice Statistics [1] completed from 2005 to 2014 that’s by far the most comprehensive study ever done regarding recidivism.

You can read more about the methodology of the study by reviewing the paper yourself, but they determined the following trends regarding recidivism:

Out of a sample of 401,288 prisoners state prisoners released in 2005

Using this study as a basepoint, one could state that the national recidivism rate is 83%.

After all, this is the most complete number available from this study and is all inclusive regarding all variables over the longest amount of time.

Finding a complete set of data indicating all of the recidivism rates by state sounds like an easy task, but unfortunately, it’s much easier said than done.

The problem with simply gathering this data is that the reports aren’t always readily available and not frequently reported.

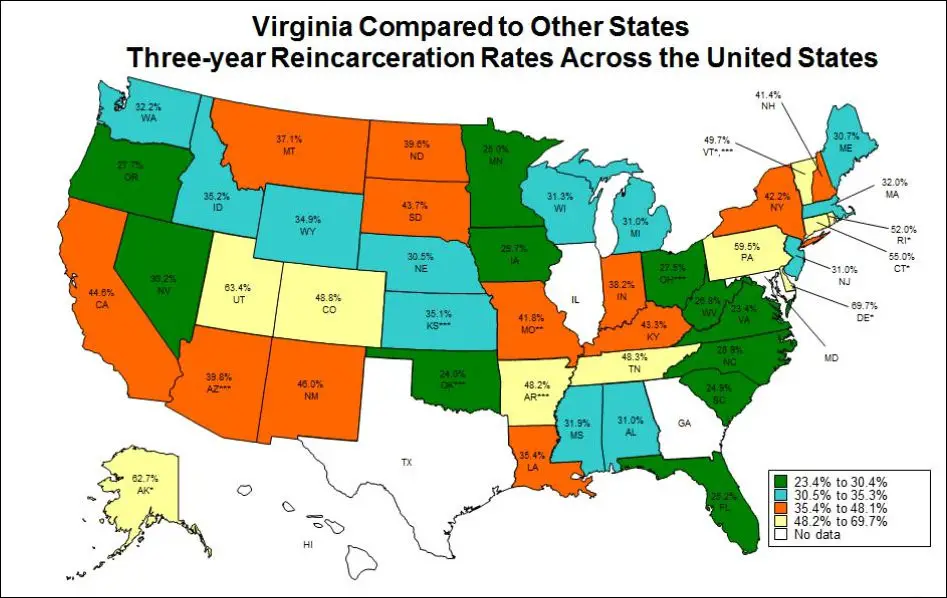

That said, the best source we could find with a data-set representative of recidivism by state is originally from the Virginia Department of Corrections.

Unfortunately though, the original article on the VDOC website has expired, but a map graphic [8] was salvaged on a third-party website.

The data was originally published in November of 2017 on the VDOC website because Virginia was celebrating having the lowest recidivism rate of any state in the United States.

It’s difficult to understand all of the details regarding the study, but it was originally published on the VDOC website, so we believe that the data is accurate.

Because the graphic is hard to read, we’ve included a list of all the states below in a sortable table with their three-year re-incarceration rate.

Please be advised that though this is the most complete study we could find, there were five states that didn’t include data for this study and they are marked as such below.

| State Name | Re-Incarceration Rate |

| Texas | N/A |

| Illinois | N/A |

| Georgia | N/A |

| Maryland | N/A |

| Hawaii | N/A |

| Delaware | 69.7% |

| Utah | 63.4% |

| Alaska | 62.7% |

| Pennsylvania | 59.5% |

| Connecticut | 55.0% |

| Rhode Island | 52.0% |

| Vermont | 49.7% |

| Colorado | 48.8% |

| Tennessee | 48.3% |

| Arkansas | 48.2% |

| New Mexico | 46.0% |

| California | 44.6% |

| South Dakota | 43.7% |

| Kentucky | 43.3% |

| New York | 42.2% |

| Missouri | 41.8% |

| New Hampshire | 41.4% |

| Arizona | 39.8% |

| North Dakota | 39.6% |

| Indiana | 38.2% |

| Montana | 37.1% |

| Louisiana | 35.4% |

| Idaho | 35.2% |

| Kansas | 35.1% |

| Wyoming | 34.9% |

| Washington | 32.2% |

| Massachusetts | 32.0% |

| Mississippi | 31.9% |

| Wisconsin | 31.3% |

| Alabama | 31.0% |

| Michigan | 31.0% |

| New Jersey | 31.0% |

| Maine | 30.7% |

| Nebraska | 30.5% |

| Nevada | 30.2% |

| Iowa | 29.7% |

| North Carolina | 28.9% |

| Oregon | 27.7% |

| Ohio | 27.5% |

| Florida | 25.2% |

| Minnesota | 25.0% |

| South Carolina | 24.9% |

| Oklahoma | 24.0% |

| Virginia | 23.4% |

Like recidivism as a whole, it’s difficult to pinpoint the repeat offenders that are sex offenders.

One of the main reasons for this is the fact that sex offenses are unlikely to be reported by their victims.

That said, this hasn’t stopped numerous parties from attempting to study recidivism for sex offenders and come to some very interesting conclusions.

One of the main fears of a sex offender is that they’ll recommit a crime of sexual nature again and impact the life of yet another victim. While this does happen, data shows that the number of sex offenders who commit a second crime of a sexual nature is significantly lower than the average recidivism rate.

In a 1994 study, the bureau of justice statistics tracked the activity of 272,111 former inmates across 15 different states to see if they would commit another sex offense within three years of release [9].

The study indicated that of the individuals tracked, the recidivism rate of sex offenders to commit another sex offense was only 3.6%.

This is the most substantive study ever done about sex offender recidivism and the results are surprising.

That said, this isn’t the only case study proving very low rates of recidivism for sex offenders.

While sex offenders are punished severely for their crimes, as they should be, data shows that the likeliness of them re-offending with another sex offense is minimal compared to the average recidivism rate.

This doesn’t mean that sex offenders don’t commit additional crimes. It just means that they’re unlikely to commit another crime of a sexual nature.

Individuals who have a dependency on drugs or are substance abusers are typically looked at as high risk for recidivism.

Unfortunately, this is for good reason.

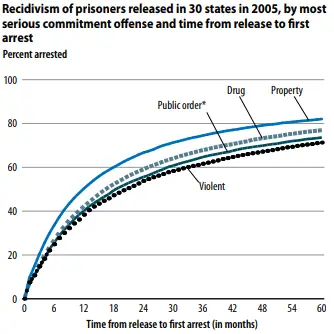

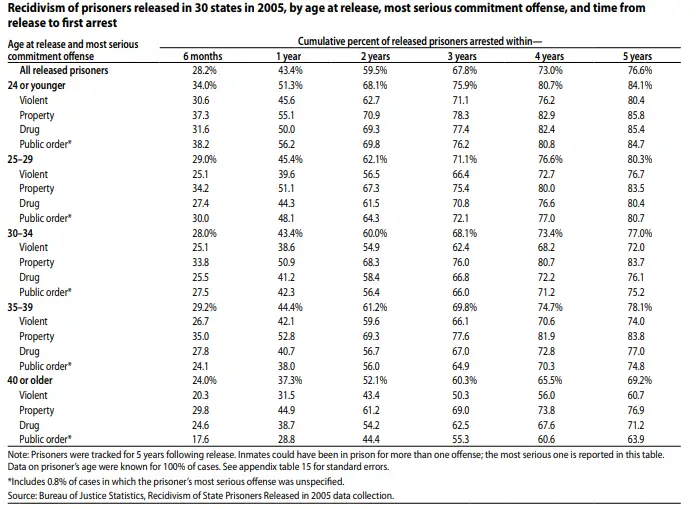

A study completed in April of 2014 [14] that followed 34,649 offenders across 30 states 2005 to 2010 found that drug offenders are the second most likely group of offenders to be arrested for a new crime.

The data showed that within 5 years of their release, those most likely to commit another crime were:

Being that this is the most complete study on drug offenders currently available, the recidivism rate for drug offenders is 76.9%.

While this is an alarming statistic, this same study compared to a very similar study developed in 1994 shows that the recidivism rate for drug offenders is actually dropping.

When compared, the 1994 study showed that 29.5% of individuals who re-offended were arrested on a drug related charge.

Conversely, in 2005, that percentage dropped to 25.6%. This is nearly a 4% drop on the total number of prisoners tracked.

The data shows that the chance of a drug offender committing another crime are as follows;

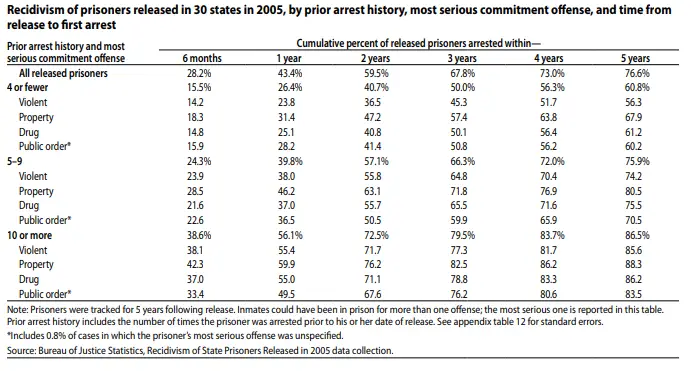

This same study also found that those who have already committed at least 5 crimes are at a significantly higher chance of committing a drug-related felony than those who have committed four or fewer crimes.

As you’ll see in the table below, the recidivism rate on drug offenses for prisoners that have four or fewer arrests in a five year time frame is 61.2%. However, the recidivism rate of those who have five or more arrests in a five year time frame is somewhere between 75.5% to 86.2%.

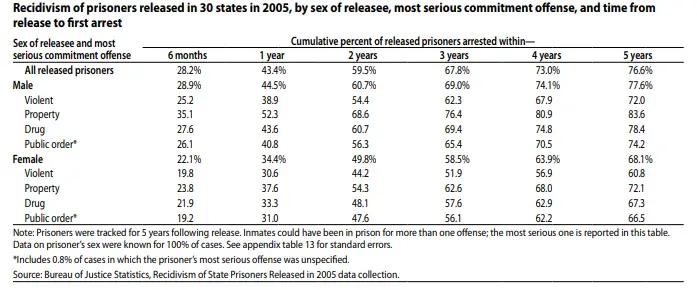

Also very interesting, this study shows that males are much more likely to commit a drug related crime upon release than females.

The table below shows that in a five year period, males re-offend on drug offenses at a rate of 78.4% while females do at a rate of 67.3%. This is over a 10% increase when males are compared to females and though we can’t state what the reasoning is for this, it’s an interesting statistic.

The last interesting data point from this study that we want to point out below is that the older an individual is, the less likely they are to commit another drug offense.

You can see that over a five year period, those that are 24 or younger re-offend on drug related charges at 85.4% However, those who are 40 or older re-offend on drug charges at 71.2%.

This shows that as individuals get older, the likelihood of them re-offend on a drug related charge falls.

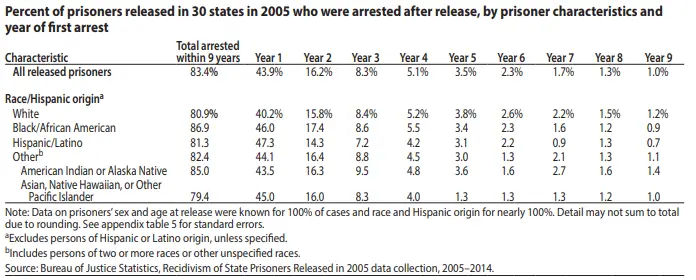

Previously we cited a study that followed the activities of 401,288 state prisoners released in 2005 over a period of 9 years to determine their likeliness to re-offend [1]. Using this same study, we’re able to view insights to determine the recidivism rate by race.

This is clearly the most rigorous study ever conducted on the subject and offers some interesting insights.

The overall recidivism rate by race over the nine year period of this study is as follows:

It’s important to note that though this study included a total of 401,288 state prisoners, 159,311 of them (39.7%) were white, 160,916 of them (40.1%) were black, and the other 81,061 (20.2%) of them were mixed in the other races.

This is important because though those with Black/African American and White origins were heavily represented in the data, other races were not, so the recidivism rates likely aren’t as accurate as they could be considering the smaller sample size of data.

The short answer is….absolutely.

You’d be hard-pressed to find a single individual who would state that recidivism isn’t a problem. When criminals continually commit crimes, it makes the United States, and the world, a more dangerous place.

That said, a better question to ask is who is responsible to correct recidivism?

The immediate answer is the individuals who commit the crimes. However, the answer is much more complex than that.

“The U.S. has five percent of the world’s population yet incarcerates 25% of the world’s prisoners, incarcerating at a rate 4 to 7 times higher than other Western nations. This corrections system impacts American taxpayers over $80 billion per year [13].”

This statistic alone shows that the United States has a mass incarceration problem, which leads to a high recidivism problem.

While we can’t possibly solve recidivism in a single guide, it’s obvious that a few things have to occur to lower this rate.

Sources:

South Dakota lawmakers explore shifting responsibility for inmate legal defense fees from counties to the state.

Montana correctional facilities address heating challenges during sub-zero temperatures by implementing emergency measures and repairs.

Cal State LA secures a $900K grant for prison to careers initiative, linking graduates with employment opportunities after incarceration.